Between 1840 and 1870, roughly 400,000 people attempted the Oregon Trail. Approximately 10,000 to 20,000 never reached the other side. That's a death rate of 2.5% to 5%—better odds than many emigrants expected, worse than any modern government would tolerate for infrastructure. To put it in perspective, if a highway killed 2.5% of travelers, it would close within hours. The Oregon Trail operated for three decades.

These numbers tell one story. The details tell another.

This is the brutal math of America's most famous emigrant route: what the journey actually cost in lives, health, money, and suffering. No romantic narratives, no heroic myths—just the cold calculations that determined who lived, who died, and who reached Oregon only to realize the gamble hadn't paid off.

The Numbers Game: Who Went, Who Died, Why

Peak Traffic Years:

- 1843: 875 emigrants (first major organized wagon train)

- 1847: 4,000-5,000 (Oregon fever spreads)

- 1849: 55,000 (California Gold Rush diverts many to southern routes)

- 1850: 44,000

- 1852: 50,000 (peak year for Oregon Trail proper)

- 1860s: Declining numbers as Civil War disrupts migration

- 1869: Transcontinental railroad completed; wagon traffic plummets

- 1883: Wagon trains rare; most emigrants travel by rail

The 1883 setting of Taylor Sheridan's series represents an anachronism. By that year, continuing to use wagons marked a family as either desperately poor, stubbornly traditional, or bound for a remote destination unreachable by rail. Western historian Michael Grauer confirmed this, noting that most 1883 travelers took trains, not covered wagons.

Death Rate Breakdown by Cause:

- Cholera, dysentery, and typhoid: 60-70% of deaths

- Accidents (drownings, wagon rollovers, gunshots, stampedes): 20-25%

- Exposure and starvation: 5-10%

- Childbirth complications: 2-4%

- Native American conflicts: 3-4%

- Other causes (snakebites, lightning, scurvy, etc.): 5-8%

The Hollywood version inverts this reality. Dramatic arrow attacks make better television than accurate depictions of people dying slowly from diarrhea. 1883 includes multiple violent encounters with Native Americans, reflective of genre expectations rather than statistical likelihood. Most emigrants never experienced hostile action from Indigenous peoples; they were far more likely to engage in trade.

Age and Vulnerability:

Children under 10: Highest death rate, particularly infants and toddlers

Adults 20-40: Lowest death rate (healthiest, most resilient cohort)

Adults over 50: Elevated death rate (less stamina, existing health issues)

Pregnant women: Significantly elevated death rate

Roughly one grave in four belonged to a child under 10. Parents faced agonizing choices: turn back and abandon their land claim, or press forward knowing each mile increased the chance of burying another child.

The Disease Math: How Water Killed Thousands

The Oregon Trail's deadliest stretch wasn't the mountains or the desert. It was the Platte River Road—relatively flat, well-watered terrain that seemed innocuous. The Platte's shallow, muddy water served as the trail's highway from Nebraska into Wyoming. It also served as sewer, cemetery, and cholera incubator.

The Contamination Cascade:

- Concentration Effect: Wagon trains traveled in groups of 20-100 wagons for safety and mutual assistance. But concentrating hundreds of people and thousands of animals along a single river system created sanitation disasters. Human waste, animal waste, and corpses all entered the water supply.

- Cholera Dynamics: The bacterium Vibrio cholerae spreads through fecal-oral transmission—exactly what happened when people drew drinking water downstream from where others had camped. One infected person could contaminate water sources for miles. In 1849 and 1850, massive cholera epidemics swept the trail, killing thousands.

- Cascading Timing: Spring departure was essential—leave too early and you'd encounter snow in the mountains; leave too late and you'd face the same problem on the other end. This compressed most wagon trains into a six-week departure window (late April through early June). The timing meant thousands of people traveled the same route at nearly the same pace, creating a human pipeline of contamination.

- Impossible Prevention: Germ theory wasn't yet understood. Emigrants knew that "bad water" caused disease, but they didn't know why boiling helped or that the clear mountain stream might be safer than the muddy Platte. Many practices actually spread disease: washing clothes in drinking water sources, dumping waste just upstream of camp, failing to isolate sick individuals.

Cholera's Timeline:

- Exposure to contaminated water

- 12 hours to 5 days: incubation period (person may be traveling, contaminating new water sources)

- Sudden onset: severe diarrhea, vomiting, muscle cramps

- 2 hours to 24 hours: without treatment, dehydration can kill

- Death rate: 50-70% of infected individuals in trail conditions

Emigrants described the horror: a person healthy at breakfast, dead by sunset. Families buried loved ones hastily and moved on—staying meant risking exposure for others. Cholera killed without warning or mercy, and no frontier medicine could stop it.

Dysentery and Typhoid:

These slower killers claimed more total victims. Dysentery (bacterial or amoebic infection causing severe diarrhea) wore people down through weeks of suffering. Typhoid fever progressed through stages: high fever, delirium, intestinal bleeding, then either recovery or death after three to four weeks.

Both diseases spread through poor sanitation and contaminated food. Both thrived in trail conditions: limited water for washing, no refrigeration, exhausted people handling food with dirty hands, flies everywhere, inadequate cooking that left bacteria alive in partially-cooked meat.

The Financial Math: What "Free Land" Actually Cost

The Homestead Act of 1862 promised 160 acres free to anyone who would settle and improve the land for five years. The actual cost? For most families, everything they owned.

Pre-Departure Costs:

- Wagon: $85-$100 (equivalent to $2,500-$3,000 today)

- Oxen team (4-6 animals): $200-$300

- Provisions for six months: $150-$300

- Tools, equipment, clothing: $50-$100

- Filing fees and legal costs: $20-$50

- Total outfit cost: $500-$900 (roughly $15,000-$27,000 in 2024 dollars)

This represented the total savings of a middle-class farm family. Poorer families often couldn't afford the journey at all. Wealthier families brought extra animals, hired help, and carried capital to establish farms quickly.

Hidden Costs:

- Selling existing property: Often at a loss, as sellers had weak negotiating position

- Lost income: Six months of no earnings

- Health deterioration: Even survivors often arrived ill, exhausted, or injured

- Lost possessions: Overloaded wagons forced families to abandon property worth hundreds of dollars

- Animal losses: Many families arrived with half or fewer of their starting animals, requiring expensive purchases to farm the new claim

Homesteading Costs:

Once you reached Oregon (or Montana, Wyoming, Dakota Territory, etc.), the "free" 160 acres required:

- Building a dwelling: $100-$500 in materials and labor

- Breaking prairie sod: Backbreaking work requiring plow, animals, and months of effort

- Fencing: Essential for crops and livestock, expensive in timber-scarce regions

- Seed, tools, and livestock: $200-$500

- Surviving until first harvest: 6-12 months of food, clothing, and supplies

- Total establishment costs: $500-$2,000+

Many families arrived broke, having spent everything on the journey. Without capital to establish a productive farm, they faced years of subsistence living or total failure.

Failure Rate:

Approximately 60% of homestead claims were never "proved up"—claimants abandoned them before the five-year requirement. Reasons varied:

- Inadequate water

- Soil unsuitable for farming

- Insufficient capital to improve land

- Isolation and loneliness

- Harsh weather and crop failures

- Better opportunities elsewhere

The Oregon Trail emigrants who survived the journey often faced a second trial: turning raw land into productive farms without resources, experience, or support. Many failed. Some died trying. Others gave up and moved to towns, becoming laborers instead of landowners.

The Time Math: Six Months of 15-Hour Days

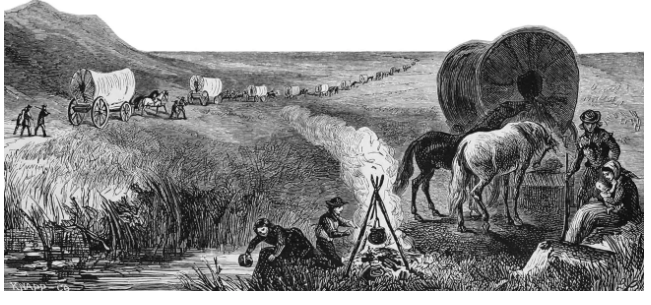

A typical Oregon Trail journey required 5-6 months—roughly 150-180 days covering 2,170 miles. The math works out to about 12-14 miles per day, which sounds manageable until you understand the reality.

Daily Schedule:

- 4:00-5:00 AM: Wake, start fires, cook breakfast

- 6:00-7:00 AM: Break camp, load wagons, hitch animals

- 7:00 AM-12:00 PM: Travel (5-7 miles)

- 12:00-2:00 PM: Noon stop (rest animals, quick meal)

- 2:00-6:00 PM: Travel (5-7 miles)

- 6:00-8:00 PM: Make camp, cook dinner, tend animals, repairs

- 8:00-10:00 PM: Evening chores, mending, preparing for next day

- 10:00 PM: Sleep (if you're lucky)

Total working time: 15-18 hours daily

This continued for six months. No days off. No hotels. No restaurants. Every meal cooked over a campfire. Every possession packed and unpacked daily. Every river crossed with improvised ferries or dangerous fording. Every breakdown repaired with limited tools and materials.

Physical Toll:

- Walking 12-14 miles daily (most people walked; riding was reserved for the sick or injured)

- Persistent dust irritation causing respiratory problems

- Inadequate nutrition causing scurvy, fatigue, and weakness

- Sleep deprivation from early starts and late finishes

- Injury accumulation (blisters, sprains, cuts) with limited medical care

- Psychological stress from constant vigilance and loss

Diaries describe the cumulative exhaustion. Early trail entries are detailed and optimistic. By mid-journey, entries become sparse, noting only miles traveled and conditions. Late-trail entries are sometimes just: "Made 12 miles. Two cattle died. Weather cold."

The Survival Math: Making the Right Choices

Success on the Oregon Trail often came down to decisions made before departure and in critical moments.

Critical Pre-Departure Decisions:

- Timing: Leave in late April or early May. Earlier risked snow in mountains; later risked the same on the back end plus insufficient grass for animals in the desert.

- Animals: Oxen over horses or mules. Oxen cost less, ate prairie grass (horses needed grain), pulled heavier loads, and could be eaten in emergencies. They were slower but more reliable.

- Wagon Weight: Ruthlessly minimize load. Extra weight killed animals; dead animals stranded families. Many emigrants packed as if moving a household when they should have packed as if backpacking.

- Company Selection: Travel with competent, compatible people. Wagon trains required cooperation, shared labor, and difficult collective decisions. The wrong company could doom everyone.

- Guide Selection: Experienced guides knew water sources, river crossings, shortcut risks, and timing. Incompetent or dishonest guides killed people through bad advice.

Critical Trail Decisions:

- Pace Management: Push animals too hard early and they'd die before the mountains. Travel too slowly and you'd hit snow. The correct pace—steady, modest mileage, adequate rest—required discipline and experience.

- Water Assessment: Which water sources were safe? How to identify cholera risk? Where to find water in desert stretches? These decisions determined survival.

- Risk vs. Shortcut: Promotional literature and unscrupulous guides touted "shortcuts" that promised saved time. Most cost time and lives—the Donner Party's disaster stemmed from taking the Hastings Cutoff. The safe choice was the known route, even if longer.

- When to Abandon Property: Every emigrant faced this calculation: What do I abandon to save the animals? Families jettisoned furniture, books, tools, clothing—anything to lighten loads. Those who refused to abandon property often lost animals, stranding themselves.

- Sick Member Dilemma: If someone fell seriously ill, should the family stay or go? Staying risked exposing others and missing weather windows. Going meant leaving the sick person behind (sometimes with one family member to care for them) or moving them despite suffering. There were no good answers.

The Myth vs. Reality Math

Hollywood Version:

- Constant Native American attacks

- Dramatic confrontations and heroic last stands

- Beautiful women in clean dresses

- Healthy, well-fed travelers

- Clear heroes and villains

- Triumphant arrival

Historical Reality:

- Most emigrants never saw hostile Native Americans

- Cholera and dysentery killed far more than violence

- Everyone was dirty, exhausted, and often sick

- Malnutrition and vitamin deficiency were universal

- Moral situations were complex and ambiguous

- Many arrivals immediately regretted the decision

1883 splits the difference. The show includes historically accurate elements: German immigrants, women's labor, crushing exhaustion, the brutality of river crossings, the randomness of death. It also includes genre-required elements: frequent violence, compressed timeline, exaggerated casualty rate, dramatic confrontations.

The series' strength lies in refusing triumphalism. Most characters die or fail. The promised land proves harsh and unforgiving. The journey breaks as many people as it makes. This emotional truth—that westward expansion mixed suffering with aspiration—matters more than technical accuracy about wagon train frequency in 1883.

What the Numbers Can't Capture

Statistics flatten human experience. Behind every number was a person:

- The mother who gave birth on the trail and walked again three days later, baby strapped to her back

- The father who buried his son in an unmarked grave and kept walking because stopping meant dooming the living children

- The teenager who took over as wagon driver when her father died, navigating by stars and instinct

- The elderly grandparent who insisted on making the journey and somehow survived when younger, healthier people didn't

- The immigrant family who spoke no English, understanding nothing of American politics or Native American relations, thrust into the middle of conflicts they didn't comprehend

These people wagered everything on a government's promise of free land. For roughly half, the gamble paid off—they established farms, built communities, and created generational wealth. For the others, the Oregon Trail represented the worst decision of their lives: financial ruin, family death, or their own grave in unmarked prairie.

The brutal math of the Oregon Trail adds up to a simple equation: extraordinary human courage and suffering, deployed in service of continental conquest, resulting in the displacement of Native peoples and the transformation of American geography. The emigrants weren't villains—most were desperately poor families seeking survival. But their individual struggles advanced a larger project of dispossession that made the trail possible in the first place.

That's the math that matters most: not the death rate or the cost in dollars, but the calculation of whose dreams got priority, whose land got taken, and who paid the price for American expansion. The Oregon Trail emigrants paid in lives and suffering. Native peoples paid in homelands and cultures. We're still calculating the interest on that debt.

1883 ended with Elsa Dutton's voiceover promising that in seven generations, the land would return to those from whom it was taken. Yellowstone concluded with exactly that return. If only the real math worked that cleanly.