More About Yellowstone Universe...

The Ticking Clock and the Unfulfilled Promise

In the mythology of the Yellowstone universe, time moves in mysterious ways. Sometimes it stretches across generations, connecting Tim McGraw's weathered James Dutton to Kevin Costner's imperious John Dutton III through blood and land and an almost mystical sense of inevitability. Other times, it compresses brutally, cutting stories short just when they seem poised to expand into something larger, leaving audiences bereft and bewildered in equal measure.

The announcement of 1944, Taylor Sheridan's third period prequel in the Yellowstone franchise, arrived in 2023 with the usual fanfare and promise. Yet as of late 2025, the project remains shrouded in uncertainty—no cast announcements, no production timeline, no teaser images of period-appropriate costumes or Montana vistas bathed in golden-hour light. While sister projects like The Dutton Ranch (the Beth and Rip continuation) and Y: Marshals (Kayce Dutton's procedural pivot) surge forward into production, 1944 languishes in development limbo, its fate increasingly tied to a countdown clock that has nothing to do with narrative pacing and everything to do with corporate contracts.

The irony is exquisite: the very quality that frustrated fans most about Sheridan's previous prequels—their ruthlessly compact storytelling, their refusal to overstay their welcome, their tendency to end just when audiences craved more—may be precisely what saves 1944 from oblivion. In an entertainment landscape where Sheridan's 2028 departure from Paramount looms like a narrative climax no one asked for, brevity isn't just an artistic choice anymore. It's a survival strategy.

The Pattern Established: When "Limited Series" Actually Means Limited

To understand the peculiar predicament facing 1944, we must first reckon with the precedent Sheridan established with his first two Yellowstone prequels. 1883, which premiered to rapturous acclaim in 2021, told the origin story of the Dutton empire through ten episodes of brutal, beautiful television. The series followed James and Margaret Dutton—portrayed with raw authenticity by country music royalty Tim McGraw and Faith Hill—as they shepherded their family along a harrowing variant of the Oregon Trail, seeking the land that would become their legacy.

The show was marketed as a limited series, and Sheridan delivered on that promise with an almost ascetic discipline. Ten episodes, no more. The finale, which saw young Elsa Dutton (Isabel May) succumb to the septic wound that had doomed her since episode nine, was devastating precisely because it was final. There would be no miracle recoveries, no last-minute reprieves, no second season to soften the blow. When Elsa's voiceover faded and the credits rolled on that tenth hour, the story was complete—a perfectly self-contained tragedy about sacrifice, survival, and the blood price of American expansion.

Fans were devastated. Online forums erupted with pleas for continuation, petitions for resurrection, bargaining for just a few more episodes to ease the pain of separation. But Sheridan, having told the story he set out to tell, moved on. The decisiveness was both admirable and infuriating.

1923 followed a similar trajectory, though with slightly more elasticity. Originally conceived as a single ten-episode season paralleling 1883's structure, the series was split during production into two shorter seasons: eight episodes initially, followed by a seven-episode conclusion that aired in 2025. The total episode count—fifteen—represented only five more hours than 1883, yet the two-season structure created an expectation of expansiveness that the compact storytelling couldn't quite fulfill.

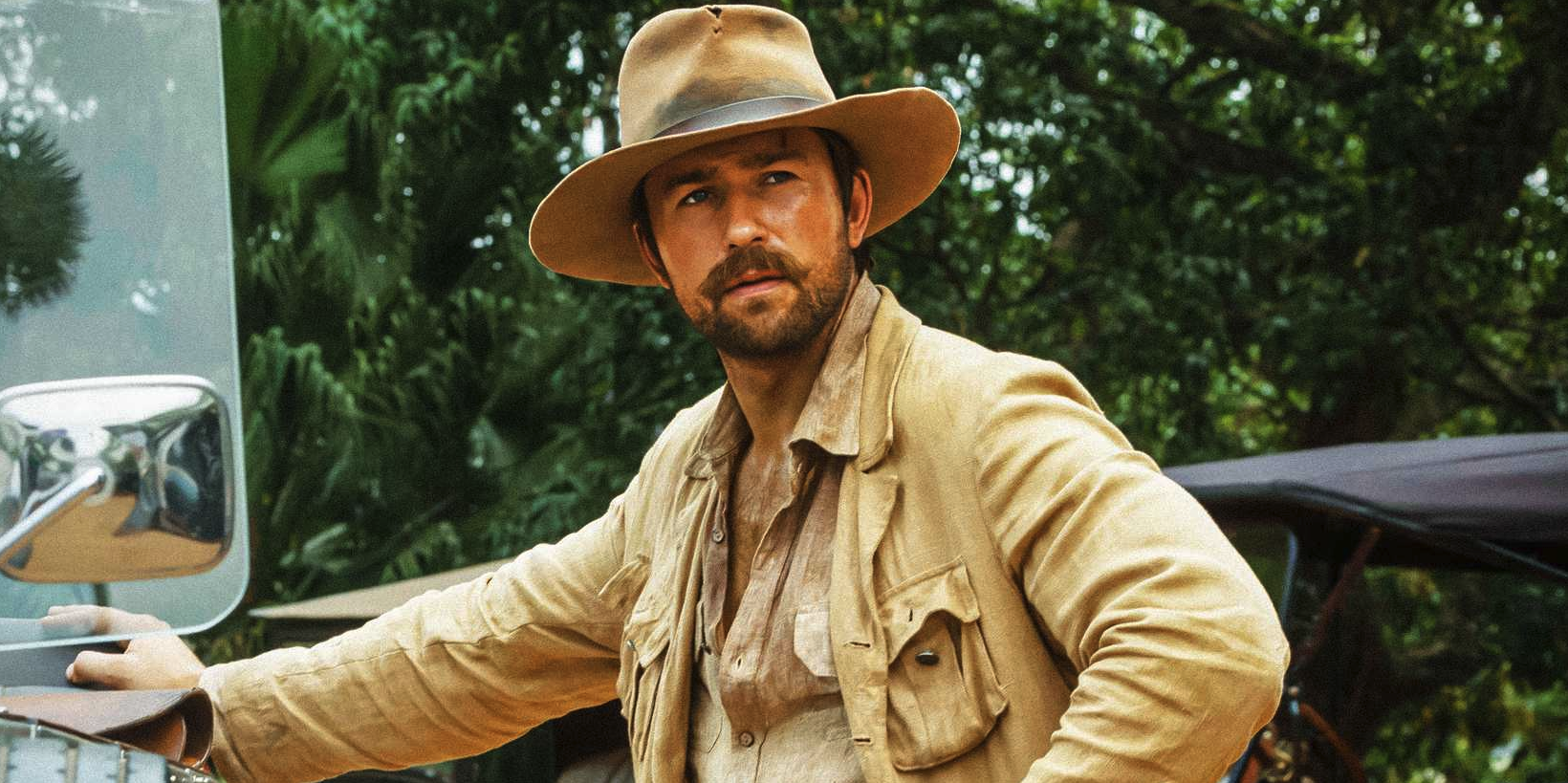

The Harrison Ford and Helen Mirren vehicle chronicled the Dutton family during the Prohibition era, forty years after James and Margaret's journey. It was a different kind of trial—not the elemental struggle against nature that defined 1883, but rather the grinding institutional violence of the early twentieth century: land wars, generational trauma, the systematic brutalization of Indigenous peoples through the Indian boarding school system. The show's emotional core, however, rested with Spencer Dutton (Brandon Sklenar), Jacob and Cara's nephew, a traumatized World War I veteran turned African game hunter who spent much of the series desperately trying to return home to Montana.

Spencer's journey—and his doomed romance with Alexandra (Julia Schlaepfer)—became the thread that kept audiences most invested. Which made the series finale's resolution both narratively satisfying and emotionally gutting: Alexandra died in childbirth mere hours after delivering John Dutton II, the grandfather of Costner's character in the flagship series. Spencer lived, but hollowed out, having lost everything in the process of fulfilling his family obligation.

Again, fans wanted more. Spencer's story felt incomplete despite its technical resolution. Sklenar himself acknowledged the emotional weight of the character: "It has affected who I am, it has changed who I am," he told Variety, adding, "So I would love to continue to do it in any capacity if I could." The actor's openness to reprising the role—even joking about aging up "with extra crows feet and frosted tips" for a potential 1944 appearance—only intensified the sense that something valuable had been left unfinished.

The Curse That Might Be a Blessing

Here's where the paradox deepens. The "problematic trend" identified by commentators—Sheridan's refusal to extend these period pieces beyond their natural narrative boundaries—has been a source of consistent frustration for the Yellowstone fandom. Unlike the sprawling, multi-season arcs of prestige television's golden age (your

Breaking Bads, your Game of Thrones), these prequels operate on a different temporal economy. They're closer to literary novels than ongoing serials, with clearly defined beginnings, middles, and ends.

What 1944 Could Be (And Should Be)

The historical setting offers tantalizing narrative possibilities. 1944 was a pivotal year in World War II—D-Day, the liberation of France, the beginning of the end for Nazi Germany. But the home front, particularly in rural Montana, experienced the war differently than coastal urban centers. Ranch labor was scarce, with young men shipped overseas. The economy was in flux, with wartime rationing and industrial priorities reshaping daily life. Native American communities, already marginalized, faced additional pressures and complications.

The Comparative Landscape: How Other Universes Handle Expansion

To fully appreciate the unique approach Sheridan has taken with the Yellowstone prequels, it's worth examining how other television franchises have handled similar expansionist impulses. The results are instructive—and not always encouraging.

The Spencer Dutton Question: Closure vs. Continuation

Brandon Sklenar's potential involvement in 1944 deserves special attention because it crystallizes the central tension at the heart of this discussion. Spencer Dutton's story technically concluded in 1923. He survived. He made it home. He lost everything that mattered—his wife, his unborn child, years of his life—but he fulfilled his obligation to the family. From a purely narrative perspective, his arc is complete.

Conclusion: The Virtue of Endings

In 2017, the film critic Emily VanDerWerff wrote an essay about television's growing inability to end well. She argued that streaming platforms' content demands and audiences' resistance to closure were creating a television landscape where shows either got cancelled prematurely (leaving audiences unsatisfied) or ran far too long (leaving audiences exhausted). The sweet spot—a complete story told in the right amount of time—was becoming vanishingly rare.

Taylor Sheridan's Yellowstone prequels represent a sustained argument for the continued viability of that sweet spot. 1883 told its story in ten episodes and ended. 1923 took fifteen episodes and ended. Both conclusions left audiences wanting more, but that wanting wasn't evidence of failure—it was evidence of success. The shows had created worlds and characters compelling enough to make separation painful.

1944, should it materialize within Sheridan's dwindling Paramount timeline, faces immense pressure to deliver. It must honor the precedent established by its predecessors while telling its own story. It must potentially provide closure for beloved characters like Spencer Dutton while introducing new ones. It must navigate the complex history of 1940s America with the same clear-eyed moral seriousness that characterized earlier entries.

And it must do all of this in, most likely, ten to fifteen episodes. Not because of artistic vision primarily, but because of corporate logistics and contractual deadlines.

Yet here's the paradox one final time: this constraint may be precisely what makes 1944 work. The pressure to be concise, to be efficient, to tell a complete story in limited time has produced some of the finest television of the streaming era. Chernobyl. The Queen's Gambit. Midnight Mass. These shows understood that television doesn't need to be forever to be great.

If 1944 embraces the same discipline that made 1883 and 1923 so memorable—if it tells a focused, powerful story about a specific moment in time and then ends—it won't just avoid the pitfalls of endless serialization. It will demonstrate that the supposed curse of Yellowstone's prequels was a blessing all along.

Because in a television landscape increasingly defined by more—more episodes, more seasons, more spinoffs, more everything—there's something almost revolutionary about a creator who still believes in the power of enough. Taylor Sheridan's "problematic trend" isn't a bug. It's a feature. And 1944, if it happens, should lean into that feature as hard as possible.

The clock is ticking. The deadline is 2028. The window for 1944 to exist is narrow and closing. But perhaps that urgency—the knowledge that this story must be told quickly or not at all—is exactly what will make it sing. Not despite its brevity, but because of it.

In the end, the Dutton family saga has always been about survival against overwhelming odds, about making the most of limited resources, about understanding that every ending contains the seeds of the next beginning. If 1944 internalizes those themes in its very structure—a complete, compressed narrative that knows when to end—it won't just continue the Yellowstone legacy. It will perfect it.